Feature

Forensics in Fiction

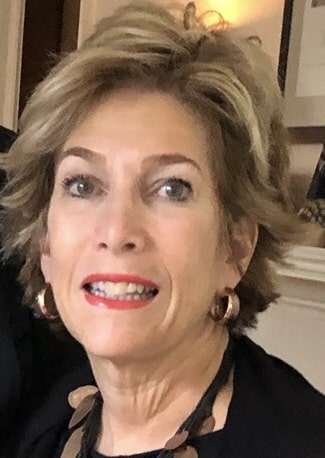

Trisha Donovan

In ancient Babylon, the Code of Hammurabi required proof of guilt before a citizen could be convicted of a crime. Unfortunately, that often involved throwing the accused into the Euphrates River. If he drowned, he was guilty; surviving this “test” meant he was innocent. It was common knowledge then that the gods would never allow the wrongly accused to drown.

That might shock us today, but it’s only been a few hundred years since most governments stopped using torture to obtain confessions. In the 18th century, the Age of Enlightenment brought sweeping changes in law and science. Changes that profoundly affected the way we determine guilt. Or prove innocence.

Modern policing methods and the use of forensics—applying scientific principles and techniques to collect, examine, and analyze physical evidence of a crime—followed in the 19th century. Investigative tools included fingerprint analysis, a test for blood, photographic documentation of a crime scene, blood-typing, ballistics, toxicology, and the microscopic examination of evidence. But “junk science,” like phrenology, which counted the bumps on a suspect’s head to establish criminality, was also popular.

The Birth of Forensics in Fiction

In 1841, the first detective story, Edgar Allan Poe’s Murders in the Rue Morgue, appeared. His protagonist, Auguste Dupin, used logical deduction to examine the crime scene and determine the killer. In its sequel, The Mystery of Marie Roget, Dupin debunked various newspapers’ theories about the murder of a young woman by focusing on the condition of her clothing, the body’s state of decomposition, and the death interval. Sherlock Holmes, Hercule Poirot, and Nero Wolfe fit this type of cerebral detective, with a friend like Dr. Watson or an employee like Archie Goodwin as the book’s narrator.

In 1910, Edmond Locard, a French criminologist, medical doctor and lawyer, created the first crime lab. He also established the basic tenet of forensic science: An “exchange of evidence” occurs whenever anyone—perpetrators, victims, witnesses, and police staff—enter and leave a crime scene. The first U.S. lab didn’t exist until 1924 and was one of many law enforcement innovations created by Berkley police chief August Vollmer.

The FBI used this lab until establishing its own in 1932. In 1933, the Bureau became part of the Lindbergh baby kidnapping investigation. Bruno Richard Hauptmann’s trial riveted the nation with news stories of the forensic techniques performed on evidence gathered by the Bureau and local police agencies—pieces of the ladder used to reach the nursery, the baby’s nightclothes, and the notes sent to the parents. The news coverage also inspired Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express in 1934., which included this evidence in the plot.

Mid-Century Forensic Fiction

Private detectives continued to dominate mystery novels through the 1960s. American “gumshoes” were often former police officers who had to rely on old connections for ballistic and fingerprint information. Talking to witnesses and suspects became the vehicle for solving crimes, so dialogue was prominent. But the cerebral detective who explained everything at the end was no longer in vogue.

Writers like Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett salted their plots with clues, turning readers into armchair detectives who matched wits with Phillip Marlowe and Sam Spade. An exception to this was Erle Stanley Gardner’s Perry Mason. The Case of the Velvet Claws (1933) established a sub-genre of legal mysteries. As a lawyer, Mason was entitled to see all the forensic evidence that prosecutors might use to convict his client.

The 1960s and 70s produced an explosion of racial violence, civil unrest, and drug use that overwhelmed police departments everywhere. The Federal government began to pump money into law enforcement agencies, raising standards and providing police with better equipment and technology. The FBI’s Behavioral Science Unit, which profiled serial killers, was created in 1972. Police procedurals, like Ed McBain’s 87th Precinct stories and Joseph Wambaugh’s novels about LAPD cops, gave readers an inside look at police work, as well as the impact on officers’ personal lives. Private detectives still ruled, but they became more regional, dealing with crimes related to environmental concerns, urban blight, and organized crime. John D. MacDonald’s Florida protagonist, Travis McGee, and Robert B. Parker’s Boston PI, Spenser, are examples.

But a hybrid of fiction and non-fiction also began to attract readers, starting in 1966 with Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood, the story of the Clutter family’s brutal murders. One of Joseph Wambaugh’s true crime books, The Onion Field, depicted two LAPD officers’ kidnapping and the murder of one of them. Helter Skelter, about the Tate-LaBianca murders, was written by Vincent Bugliosi, the DA who prosecuted Charles Manson and his followers. And in Norman Mailer’s The Executioner’s Song, the crime spree, trial, and death of Gary Gilmore are featured. Although Mailer based his book on numerous interviews with Gilmore and family members, the others contain detailed descriptions of the forensic evidence from crime scenes used in the investigations. The authors’ use of novelistic techniques in the narratives and recreated dialogue were especially compelling.

Modern Forensics in Fiction

Since the 1980s, technological and forensic innovations have grown exponentially, making it easier to connect perpetrators to crimes. The proliferation of personal computers allowed the FBI to create cyber databases like NCIS, AFIS, and VICAP, with information on crimes, unidentified victims, fingerprints, and criminal records. Suspects’ computer hard drives, cell phones, and GPS logs also became treasure troves of damning evidence. And DNA profiling, perhaps the most important forensic tool to date, blew the lid off criminal investigations. And prosecutions that had led to wrongful convictions.

Public interest in violent crime has also grown, fueled by sensational headlines. Among book genres, crime fiction is now second only to romance novels in popularity. The myriad of sub-genres—”cozies,” police procedurals, espionage thrillers, paranormal mysteries, medical and legal mysteries, noir, and military thrillers—proves this. As do the blockbuster novels written by authors like John Grisham, Michael Connely, Tom Clancy, Dennis Lehane, Lee Childs, Patricia Cornwell, Jo Nesbo, Henning Mankel, Stieg Larsson, and Robert B. Parker, which also ended up on big and little screens.

Crime fiction based on forensic science has been a favorite of viewing audiences. Thomas Harris’ books, Red Dragon and Silence of the Lambs became big-screen successes. In addition to criminal profiling, they featured forensic entomology and forensic psychiatry. Jeffery Deaver’s criminalist, Lincoln Rhymes, starred in The Bone Collector, movie and James Patterson’s Alex Cross, a detective with a Ph.D. in psychology, in Along Came a Spider and Kiss the Girls. And in The Name of the Rose, also adapted for the movies, Umberto Ecco paid tribute to Conan Doyle with the tale of a Franciscan friar named William of Baskerville. Brother William investigates the murders of several monks at an Italian monastery in 1327, examining the crime scenes and interviewing witnesses.

Kathy Reichs’ book series about forensic anthropologist Temperance Brennan was the basis of the TV show Bones. Rizzoli and Isles sprang from Tess Gerritsen’s novels featuring a Boston homicide detective and a medical examiner. The Alienist and The Angel of Darkness by Caleb Carr, about 19th century forensic psychiatrist Laszlo Kreizler, who hunts serial killers using an early form of profiling, wowed TV audiences. And the fictional version of the FBI’s creation of its Behavioral Science Unit, detailed in John Douglas’ non-fiction book, “Mindhunter,” is also a hit TV series. Then, of course, there’s Dexter, the show that made blood spatter analysis cool and serial killers likable. It began life as Double Dexter, a book by Jeff Lindsay.

Techniques of Modern Forensic Fiction

Most crime fiction doesn’t make it to TV or movie screens but offers readers insight into forensic techniques. Michael Pronko’s award-winning series about Tokyo forensic accountant Hiroshi Shimizu is an example. A white-collar crime detective, Shimizu’s soon up to his laptop in gory murders. The Widower’s Wife, by Cate Holahan, follows an insurance investigator trying to prove that a disgraced money manager has killed his wife for a five-million-dollar payout. His Asperger’s Syndrome allows him to juggle all manner of statistics about accidents, violent deaths, and human beings.

Iris Johansen’s books feature Eve Duncan, a facial reconstructionist who helps police identify murder victims. P.J. Tracy’s Monkeewrench follows computer experts as they help detectives solve a series of murders inspired by a cyber game they created. One of Michael Connelly’s books that hasn’t become a movie—yet—is The Law of Innocence. Mickey Haller, the defense attorney from The Lincoln Lawyer, is framed for murder with switched DNA. It’s a fascinating look at the security issues surrounding companies like Ancestry and 23 and me. It also touches on the genealogy and social media tracking that detectives used to investigate the Golden State killings.

Forensic science is still relatively new, and courts have had to arbitrate problematic evidentiary issues. For example, although forensic ontology has been valuable in identifying victims through dental records, bite mark evidence has come into question. During Ted Bundy’s 1979 trial for the murder of Lisa Levy, it helped obtain a guilty verdict when an impression made of his distinctive upper teeth fit perfectly over an enlarged photo of bite marks found on the body. But DNA evidence that later exonerated several inmates convicted by such evidence caused one dental expert to admit the technique was very subjective and “as much an art as a science.”

Blood splatter criminalists who’ve received poor or minimal training have also come under fire. In 1985, Joe Bryan was convicted by a Texas jury for his wife’s murder. A detective who had taken a bloodstain analysis training course testified that a tiny smear on a flashlight “found” by Bryan’s brother-in-law was similar to stain patterns found at the crime scene. He later admitted that some of his conclusions were wrong, but Bryan spent thirty-three years in prison before being paroled. John Grisham’s 2019 novel, “The Guardians,” features a lawyer/Episcopal priest working with a non-profit organization that helps exonerate wrongly-convicted people. He ultimately frees a man whose case is similar to Joe Bryan’s.

Crime labs have also had their share of bad publicity. The FBI’s crime lab had to undergo accreditation and other significant reforms after a supervisor, Dr. Frederic Whitehurst, turned whistleblower. A Department of Justice investigation supported Whitehurst’s claims in 1994 that lab technicians were using improper and unscientific methods to analyze evidence. In 2013, Annie Dookham, a chemist with the State Lab in Boston, was convicted of falsifying drug test results. These scandals, which revealed that hundreds of suspects had been wrongly convicted, undermined the public’s confidence in forensic science.

Although advances in forensic science have made criminal investigations easier, the procedures are only as reliable as the technicians who perform them and present their findings in court. Each forensic field has needed to standardize its methodology, training, and qualification process to keep “junk science “from putting innocent people in prison.

Similarly, novels showcasing forensics are only as good as the talent and ability of their authors. Extensive research on particular techniques and a competent understanding of the science behind them is as important as plot or character development. Crime fiction readers have become more sophisticated since Hercule Poirot and his “little grey cells” solved murders in country estates or on luxury ships and trains. The best writers open a window into a violent world that most people don’t want to see.

Except vicariously.

About the Author

While finishing a Master’s degree in Criminal Justice at Georgia State University, Trisha Donovan interned at the Fulton County Medical Examiner’s Office in Atlanta. Assigned to the investigative unit, she discovered how essential the investigators’ duties were in helping the forensic pathologists determine the cause and manner of death. She was also able to observe several autopsies. This proved invaluable in toughening her up for her law enforcement career, first as a volunteer analyst in the Missing Children’s Information Center at the Georgia Bureau of Information, then as a probation officer and supervisor of officers at the Georgia Department of Corrections.

Under the name P.L. Doss, Trisha has written three forensic novels. The series’ protagonist is a death investigator for a fictitious county in Georgia. She also writes a crime fiction column called “Murder, Etc” for Smoke Signals, a regional newspaper in North Georgia. This article is an expanded version of a column published earlier by the newspaper.

More Crime Features

Criminal Fashion

Iconic Outfits and Styles in Crime Fiction

Ethics in Crime Fiction

Exploring Morality in Law and Order

Hard Case Crime

Celebrating its 20th anniversary

Advertisement