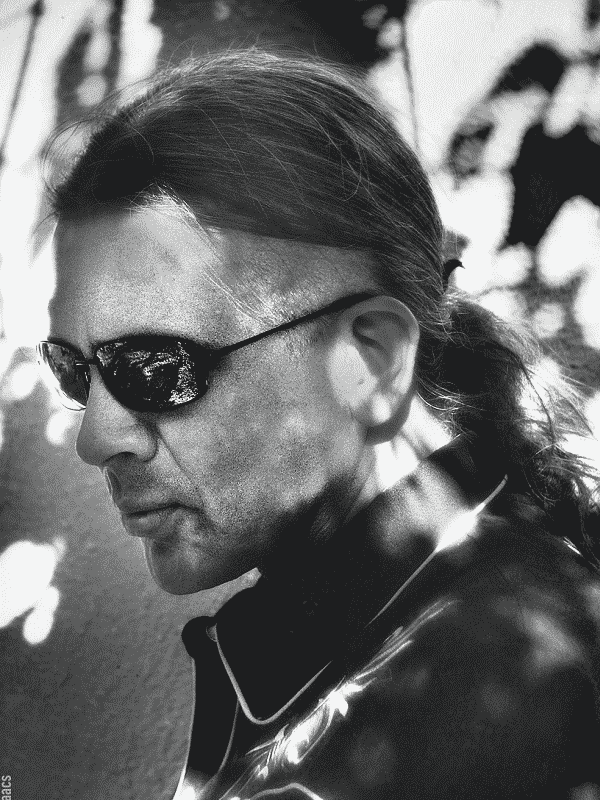

Q&A

Stephen Graham Jones

Stephen Graham Jones is the NYT bestselling author of twenty-five or thirty books. He really likes werewolves and slashers. Favorite novels change daily, but Valis and Love Medicine and Lonesome Dove and It and The Things They Carried are all usually up there somewhere. Stephen lives in Boulder, Colorado. It’s a big change from the West Texas he grew up in. He’s married with a couple kids, and probably one too many trucks.

Q. My Heart is a Chainsaw is horror at its best. On the surface, an enthralling slasher story. Levels deeper, a story about hometown, identity, change. What inspired it?

Stephen: My hometown usually comes up as “Midland, Texas,” but that’s just because where I actually grew up isn’t on the map. It’s between Midland and Stanton, and I spent more time in Stanton, probably, which, like Proofrock, is about three thousand people and feels a lot like 1962 never stopped happening. So, you’re right, My Heart is a Chainsaw is a lot about small-town life, and living, and how everybody knows everybody. Often in the slasher, when the setting is a small town, then the protagonist will be the new kid, just stumbling into this cycle of violence.

With My Heart is a Chainsaw, I wanted that same outsider status, but I also wanted to focus it through someone with insider knowledge. Enter Jade Daniels, social outcast, lifelong resident, and hardcore slasher aficionado. Slashers are how she makes sense of her world, and she’s been praying to Carpenter and Craven to please send her a Jason, a Michael, a Freddy, as she’s got some work for them to get done — and I guess that’s one place where My Heart is a Chainsaw starts, for me, inception-wise: How do you deal with your most fervent wishes suddenly coming true around you? Do you wish you could reel that last wish back in, maybe? Slashers are fun to watch and read, I mean, but . . . trying to live through one? It’s a brutal, violent cycle, and feels a lot different from the center than it does from the outside.

Q. How does My Heart is a Chainsaw not just exist at the top of the genre, but also dive deeper as a meta-exploration of the genre?

Stephen: You know how, for a long time, people in zombie stories had never seen Night of the Living Dead? Or, it’s not that they just hadn’t seen it, it’s that it doesn’t seem to exist in their world. They don’t say “zombie” when they see the dead walking around, I mean. It was that way for a long time, but then storytellers figured out that it was scarier if these characters were actually from our world, where zombie movies have proliferated. It’s the same with the slasher. Scream really popularized these teens at the center of things being conversant in slasher conventions and tropes, which made it feel a lot more like Ghostface could, some Friday night, call us. But knowing the genre you’re in doesn’t necessarily insulate you from that genre, as Jade, the protagonist of My Heart is a Chainsaw, has to learn. It’s like, standing out on the interstate, you might know the make, model, and history of the truck bearing down on you, but that’s not knowledge that’s going to keep that truck from hitting you. It just allows you to narrate it as it’s happening. Jade doesn’t make the rules, she just happens to know them all — and she thinks that’s going to keep her safe. But, Randy, the know-it-all from Scream, ends up getting it in Scream 2, doesn’t he? That truck’s going to hit you whether you see it coming or not.

Q. What do you read, both within and outside of horror? How does what you read impact your writing voice?

Stephen: I read all the horror I can, of course, and have been since . . . since forever, feels like. Outside of horror, I read everything else: science fiction, essays, paleoanthropology, on and on. Walking through other fields, burrs stick to your pants legs, and then when you come back to your home field — horror, for me — those burrs fall off like they’re designed to do, become the seeds they were all along, and grow up into these strange and unexpected plants. Specifically talking My Heart is a Chainsaw, I think it comes in part from Jeffrey Eugenides’ The Virgin Suicides, which I read a lot in the nineties. I was smitten with the delivery method that book uses and thought it was something I could port out, use for horror. The first drafts of My Heart is a Chainsaw were written with that same delivery method — “we,” not “I” — and I still feel remnants of that alien DNA when I look at certain passages.

Q. Your writing is famous for eliciting visceral, honest reactions from readers that puts you at the peak of horror authors. What drives you to write this way? Could you jolt your readership as well if you wrote in another genre?

Stephen: I would definitely try to jolt them that same way, yeah. And, I know it’s possible because I’ve seen it done. There’s a narrative escalation in Ian McEwan’s Atonement, say, that’s as sharp and visceral a turn as anything you’ll see in horror, there’s some developments in DM Thomas’s The White Hotel that make you shudder, and there’s some dread in Louise Erdrich’s work that’s tacky and uncomfortable and wrong and wonderful — that’s perfect, I’m saying. I’d hope that, with enough work, and if denied eviscerations and decapitations and the like, I could stage something similar. The ideal is always that you want the reader to drop the book in shock, right? Whatever genre you’re working in. And, yeah, maybe they pick it back up, hold it close for years afterwards, but if you can shock them initially, and in a medium — prose fiction — where they’re actually the ones controlling the pace, the page-turns, then . . . that’s when you’re cooking with fire, I’d say.

Q. The Only Good Indians is probably your best-known hit. How does My Heart is a Chainsaw build off the success of that story?

Stephen: The Only Good Indians is a slasher through and through. Four guys commit a prank, and, years later, a spirit of vengeances comes to rebalance the scales of justice, violently. So, what The Only Good Indians uses as a scaffolding, a structure, a dynamic, My Heart is a Chainsaw makes overt, via Jade Daniels being clued in to the dynamic unreeling around her and trying to loop her in. But they’re both slashers at heart, and by the masks they wear, the wreckage they leave behind. Balancing those scales of justice is never pretty, I mean. It feels good in intention, it feels pure and righteous, but, the morning after . . . things aren’t so pretty. However, seeing that sunrise, always, is a final girl. She’s stood up to her bullies, she’s been reborn in blood, she’s figured out who she is and how to live — she’s a model for us all. Final girls tell us how to survive, they chart out the price of that survival for us, and they show us that there’s hope, that there’s a light way down at the end of the tunnel, if only we’re willing to fight through to it.

Q. What are you working on now?

Stephen: Just finished the first draft of another slasher, I’m in rewrites on a haunted house novel, I’ve got another slasher novel I’ll start rewriting soon, and I’ve got my writing fingers in a lot of other ink pots, as well: television, film, comics, and — always — short stories and flash fiction. I’ll never stop writing short stories and flash fiction.

Stephen Graham Jones's Latest

My Heart is a Chainsaw

Jade Daniels is an angry, half-Indian outcast with an abusive father, an absent mother, and an entire town that wants nothing to do with her. She lives in her own world, a world in which protection comes from an unusual source: horror movies…especially the ones where a masked killer seeks revenge on a world that wronged them. And Jade narrates the quirky history of Proofrock as if it is one of those movies. But when blood actually starts to spill into the waters of Indian Lake, she pulls us into her dizzying, encyclopedic mind of blood and masked murderers, and predicts exactly how the plot will unfold.

Yet, even as Jade drags us into her dark fever dream, a surprising and intimate portrait emerges…a portrait of the scared and traumatized little girl beneath the Jason Voorhees mask: angry, yes, but also a girl who easily cries, fiercely loves, and desperately wants a home. A girl whose feelings are too big for her body. My Heart Is a Chainsaw is her story, her homage to horror and revenge and triumph.

More Horror

Advertisement