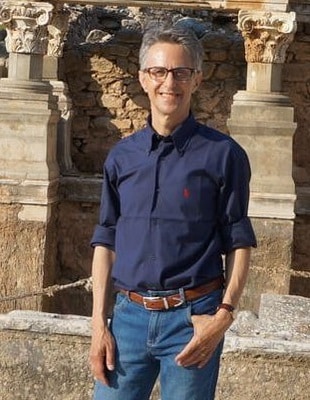

Q&A

Mitchell James Kaplan

Interview by Annette Bukowiec

Mitchell James Kaplan’s 2010 novel, By Fire, By Water, won numerous literary awards both domestically and abroad. Into The Unbounded Night, a novel of first century Rome and the destruction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem, came out September, 2020. His latest, Rhapsody, comes out today (March 2, 2021).

Q. You are a cum laude graduate of Yale University in English Literature. I’ve read all your three books and your writing is of the highest quality. But I’d like to ask you about the historical background. Did you know that you wanted to weave history into your stories from the time you were a student or did it come to you later as a part of your life’s journey?

Mitchell: In high school I was an avid reader of fiction. Not necessarily historical fiction. Classics like Hawthorne, Hesse, Mann, Dickens, etc. as well as contemporary authors. When I went to college, one of my goals was to read through all of English literature—that is, the most important works from Beowulf through the contemporary period. As you know, when you delve deep into that spectrum, you encounter a preponderance of verse up until at least the Romantic period. That poetry isn’t primarily concerned with storytelling, at least not in the way we today understand storytelling. Even great epics like Pilgrim’s Progress, The Fairie Queene, and Paradise Lost emphasize allegory and philosophy over narrative. (The idea of bringing the characters and story into the foreground pretty much originates with Shakespeare, in my opinion. But of course he’s not writing novels per se. And his poetizing abilities remain stellar—his stunning metaphors and the way he strings words together in original ways that compress meaning.)

Anyway, as a person living and breathing poetry day in and day out, I was sensitive to the music of language, and I committed passages to memory for the pleasure of it. I still wanted to be a novelist, but I had no idea what kinds of novels I would write. My first two attempts at a novel were set in the contemporary world. I would say in retrospect they were personal and experimental—and not quite “ready for prime time”—although the novelist William Styron, who occasionally hung out at Yale, did see something in my second effort that led him to provide the encouragement I needed. Speaking of Styron, he gave me a bit of advice that powerfully influenced me: “The most important thing is that your readers believe your story.”

After college I lived in Paris for seven years, working as a translator and English teacher. One day, I was sitting in the Bibliotheque Nationale just kind of surfing from one book to another (I used to do that quite a lot) and I happened upon an old book about the size of a pamphlet that contained a list of every sailor on Columbus’s first voyage in 1492 along with biographical details. I found it fascinating and when I came across “Luis de Torres,” who was characterized as “The Jew,” I was intrigued. (I knew that the Jews had been expelled from Spain shortly before Columbus’s voyage.) Then, when I explored further and came to realize how deeply intertwined were four world-changing events of the late fifteenth century— the Spanish Inquisition, the Reconquest of Granada, the Expulsion of the Jews from Spain, and the discovery of the New World—it hit me hard: This is my first real novel—it has the weight and importance that I’m looking for. The historical context and its significance appealed to me. If I did thorough research, my readers would believe my story.

Into the Unbounded Night grew out of By Fire, By Water, insofar as the research and writing of the earlier novel caused me to think a lot about Christianity and Judaism, and the context in which the split between the two had occurred. Compelled by curiosity, not yet thinking my research would result in a novel, I started reading everything I could about the period when Christianity was new.

My third novel, Rhapsody, came to me following my father’s death. He was what you might call a serious amateur clarinetist, and he used to play things like Mozart’s Clarinet Concerto and Rhapsody in Blue in the living room. One morning, a couple of months after he died, and after I had finished writing Into the Unbounded Night, my CD player was set to “random shuffle” as I was taking my coffee. There were 300 discs in that player, and Rhapsody in Blue came on. My eyes filled with tears. My dad was there in the room, playing along. And I knew that was my third novel. At that point I knew nothing about Kay Swift or James Warburg. But I knew.

I guess my point in going into all this detail is to say: I never did decide to become a historical novelist and I still don’t think of myself as a historical novelist. I think of myself as a novelist. These subjects seemed worthy of exploration and they happened to occur in the past.

It seems to me, too, that the present is part of history.

Q. I have recently read your book Into the Unbounded Night and I’m still trying to wrap my head around it, how you were able to weave such a story, with all the main and supporting characters intricately developed and the massive research that went into bringing out the historical background. Can you tell us more about how much time you spent on crafting this story and how it all came together? Did the idea of the characters come to you while doing the research?

Mitchell: My novels tend to start with an abstract question, for example: How did the divergence between Christianity and Judaism occur? As I research this first question, lots of other questions arise, such as: Why did Rome feel it was necessary to destroy the Second Temple? What was the nature of the cultural and philosophical conflicts that set Jerusalem apart from the rest of the Roman empire? How did sin become a central issue in early Christianity? What was going on in the city of Tarsus when St. Paul was a boy? Etc.

My initial research, which in the case of Into the Unbounded Night occurred over a period of a few years, was just about satisfying my curiosity, or trying to figure things out, to put together the pieces of the puzzle that emerged in my mind. Yes, the characters flow from the research; but then, when they start to come alive, the novelist’s job is to get out of their way and let them tell their stories.

That is to say: There’s a logic to the story and its mechanisms, and a psychology inherent in the characters, that do not result from conscious deliberation. They are much too detailed and nuanced for the novelist to figure out in his or her conscious mind. At a certain point it’s more about listening than thinking (as Gershwin tells Kay Swift in Rhapsody.)

I don’t try to plot everything out in detail prior to the writing, but I do try to have a clear idea of where the novel starts and where it is going. That idea takes form over a period of time. It involves research, lots of thinking, and dreaming.

By the way, I don’t take notes when I research. The important information lodges itself in my mind. The rest is just noise.

Q. Does your research take you to the places you research about? If yes, does it influence your writing in any way?

Mitchell: Before I wrote By Fire, By Water, I visited the Alhambra (in Granada, Spain) and some other relevant places. Prior to writing Into the Unbounded Night (and during the writing of it) I traveled to Rome, Jerusalem, Ephesus, and some Roman sites in the U.K. Of course, I was deeply familiar with New York City long before I wrote Rhapsody.

I didn’t go to those places with the idea that doing so would make my novels better, and I can’t say for sure that physical travel to a location enhances the novel in any way. I went to those places because I was intensely curious about them, that’s all.

Q. Do you read historical fiction or is it all non-fiction history that goes into your research to craft historical novels?

Mitchell: I read all kinds of history and fiction. I don’t care much about genre. Give me a good story, written in an interesting voice, with characters I care about (even if I don’t like them) and I’m hooked. But I do tend to shy away from novels that might influence me in terms of style, approach, or historical detail. I’m actually kind of paranoid about that because I don’t trust other novelists to do my homework for me and I don’t want to be misled.

Q. I’m eagerly awaiting your next book. Is one already in process?

Mitchell: Yes. I’ve completed a first draft of my fourth novel and of course I’m quite excited about it. It’ll be awhile, though… but as soon as we have galleys, I’ll try to make sure you get one!

Mitchell James Kaplan’s Latest

Rhapsody

One evening in 1924, Katharine “Kay” Swift—the restless but loyal society wife of wealthy banker James Warburg and a serious pianist who longs for recognition—attends a concert. The piece: Rhapsody in Blue. The composer: a brilliant, elusive young musical genius named George Gershwin.

Kay is transfixed, helpless to resist the magnetic pull of George’s talent, charm, and swagger. Their ten-year love affair, complicated by her conflicted loyalty to her husband and the twists and turns of her own musical career, ends only with George’s death from a brain tumor at the age of thirty-eight.

Set in Jazz Age New York City, this stunning work of fiction, for fans of The Paris Wife and Loving Frank, explores the timeless bond between two brilliant, strong-willed artists. George Gershwin left behind not just a body of work unmatched in popular musical history, but a woman who loved him with all her heart, knowing all the while that he belonged not to her, but to the world.

More Historical Suspense

Advertisement